Reviewing PRS literature Part 1

Published:

Today I reviewed 10 of papers on PRS literature. Part 1.

The message of this paper is in the title. They note that PRS normally measure cancer incidence, which is not always the same as mortality. If PRS do not discriminate lethal from non-lethal disease, using them to determine who to subject to a screening strategy associated with overdiagnosis is unlikely to be of benefit. If we evaluaute PRS based on mortality, we are more likely to develop clinically relevant guidance.

A PRS model using 10 SNPs associated with papillary thyroid disease was noted to be better than a control model using only clinical factors. It was also better than a model that included additional SNPs. It concluded that PRSs based on a small number of common germline variants is better for papillary thyroid cancer. Outcomes were change in AUC and risk in top decile compared to bottom decile.

Title sparking controversy. For PRS to be clinically useful, two assertions must be proven correct. The first assertion is that PRSs provides sufficient risk discrimination. The second is that this risk discrimination is meaningful in the context of absolute risk of that cancer and applicable in the context of respective tools available for prevention and early detection.

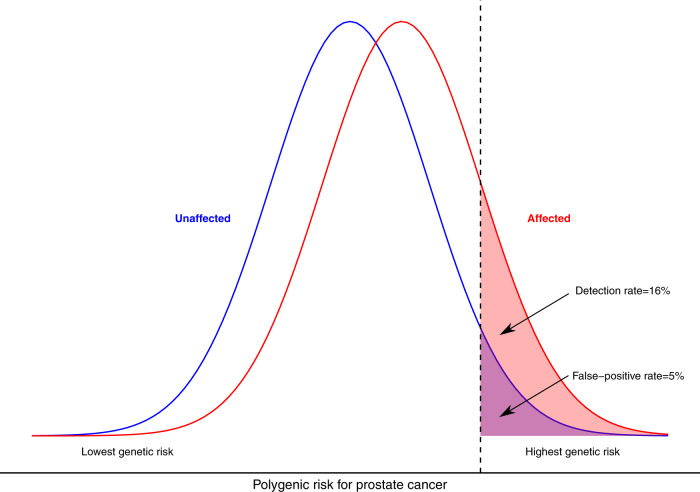

Two commonly presented measures of discrimination derived from these distributions are: (i) comparison of the RR for those at the top and bottom tails of the PRS distribution (ii) comparison for specified PRS cut-offs of the proportion of affected individuals with ‘positive’ PRS (‘detection rate’) versus the proportion of unaffected individuals falling within the same PRS score range (the ‘false-positive rate’ (1–specificity)) (Supplementary Fig. 1). For the common cancers, PRS for prostate currently leads on discriminatory performance, with RR of 14.54 between the top 5% and bottom 5% of men. This translates to a false-positive rate of 5% for a detection rate of 16%. Or, to achieve a detection rate of 50%, tolerance of a false-positive rate of 25%.

They present a figure which is helpful in understanding how to translate outcomes in PRS to clinically meaningful difference in risk.

They also note that the figure above, and for many PRS, we are discussing relative risk, but not taking into consideration absolute risk. When applying results in someone’s risk to whether they should be screened, the only important factor should ultimately be absolute risk. E.g. it doesn’t matter if someone is in the top centile for risk of adrenal cancer - because if that represents 0.01% absolute risk, screening still isn’t warranted.

PRS for melanoma show roughly 2-to-3-fold increases in risk and modest improvements in risk prediction (2–7% increases). PRS are associated with 2-fold and 3-fold increases in risk of cSCC and BCC, respectively, with small improvements (2% increase) in predictive ability. Therefore, existing data indicate that PRS may offer small, but potentially meaningful, improvements to risk prediction

The PRSs stratify breast cancer risk in women of African ancestry, with attenuated performance compared with that reported in European, Asian, and Latina populations. The PRS had odds ratio 1.27 and AUC 0.571, which are pretty bad and even worse than EUR ancestry. Future work is needed to improve breast risk stratification for women of African ancestry.

This study evaluated patients who have known BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic variants. It demonstrated that PRS using up to 313 SNP panel in these patients are strongly associated with breast cancer and epithelial ovarian cancer and predict substantial absolute risk differences for women at PRS distribution extremes.

A total of 10 studies were included in the review, which investigated 3 cancers: prostate (n = 5), colorectal (n = 3), and breast (n = 2). Of the 10 papers, 9 scored highly (score >75 on a 0-100 scale) when assessed using the quality checklist. Of the 10 studies, 8 concluded that polygenic risk-informed cancer screening was likely to be more cost-effective than alternatives. Overall, it is unclear if polygenic risk stratification will contribute to cost-effective cancer screening given the absence of robust evidence on the costs of polygenic risk stratification, the effects of differential ancestry, potential downstream economic sequalae, and how large volumes of polygenic risk data would be collected and used.

Actionability of PRS depends on several factors. First, actionability depends on the discriminative power of the score, or how well it predicts who is at risk of the disease. Second, it depends on the PRS comparative performance with respect to existing practice, as a score with good discriminative power will not be useful if there are better predictors used in the clinic. Finally, for a PRS to be useful there must also be available preventive actions. In future studies, beyond predicting cancer risk, similarly developed PRS models may be of utility in predicting prognosis or treatment resistance. We need to focus research on considering where PRS may be most discriminative and impactful at the population level, which will greatly aid in the development of new methods to overcome the challenges in the paper.

For best compatibility, it has previously been reported that GWAS and sample used for testing PRS should match in terms of ancestries. GWAS, especially in the field of cancer, often lack diversity and are predominated by European ancestry. The paper highlights that differences in the PRS distributions of these groups are amplified when PRS methods condense hundreds of thousands of variants into a single score. Yet, the PRS can be useful for risk stratification within EUR or within non-EUR individuals even though their distributions are dissimilar. To do this, a large sample size is needed, the cancer needs to be heritable, lastly it is better that even if the population has different ancestry, their geographical location is the same. I could read more into this.

The findings provide one of the earliest reports on how breast cancer PRSs are communicated to women. Key messages for communicating PRSs were identified, namely: discussing differences between polygenic and monogenic testing, the multifactorial nature of breast cancer risk, polygenic inheritance and current limitation of PRSs.